The global attention placed on Japanese brands has grown stronger in recent years.

At the heart of this is Japan’s unique perspective on manufacturing and a sincere dedication to craftsmanship, values that are deeply embodied in Grand Seiko.

In this interview, one Grand Seiko master craftsman reveals the essence of Japanese aesthetics, which are admired around the world, through close observation of another leading Japanese brands.

The first interview took place at the Suntory Yamazaki Distillery. Master watchmaker Satoshi Hiraga from the Grand Seiko “Kodo” assembly team visited Mr. Futoshi Koshiishi, a blender who works on a critical part of the whisky-making process.

The blender’s role involves using their expert sense of taste and smell to assemble multiple whiskies from various casks into a harmonious final product.

The same principle applies to mechanical watches, wherein watchmakers use their finely honed tactile sense to assemble numerous tiny parts and components into a fully functioning movement.

There are surprisingly many points in common between the blender and the watchmaker.

To create a successful blend

Never overlook even the subtle differences in each and every drop of component whisky.

Understand how they come together in perfect harmony.

Satoshi Hiraga: During the Yamazaki Distillery tour, I was surprised to learn that the type of cask used for maturation can influence the characteristics of malt whisky. Could you describe the blender’s job-how you combine different types of whisky into a final product?

Futoshi Koshiishi: A blender has three main responsibilities. The first is to maintain quality and ensure a stable supply of our existing products. We combine multiple component whiskies with distinct characteristics to create a final product with consistent quality and a well-balanced flavour. The second role is product development. The third is whisky inventory management, based on a projected balance of future supply and demand. This is a particularly important part of our work.

Hiraga: Why is that so important?

Koshiishi: Currently, we have fewer than ten blenders at Suntory, each responsible for monitoring the quality of a vast inventory of component whiskies stored across Japan. Each component whisky is carefully analysed to determine the optimal timing and product for its use. For example, a relatively young component whisky might be used for Kakubin (Square Bottle), while some of it is set aside for future releases such as Yamazaki 12 Years Old or Hibiki products. So, the blenders play a very important role in assessing the quality of each whisky and determining its appropriate distribution.

Hiraga: That means everything happens at the same time, maintaining the quality of existing products, designing new whisky blends, and selecting whiskies for both short- and long-term use. But for instance, with a product like Yamazaki 12 Years Old, the component whiskies used and their amounts are already determined, right?

Koshiishi: That’s true. For crafting the taste of Yamazaki 12 Years Old, we always use component whiskies matured in Spanish oak, Japanese Mizunara oak, and American oak casks. The blend ratio is mostly fixed. But even using the same ratio does not always produce exactly the same result. Whiskies matured in the same types of casks, stored in the same warehouse, for the same period of time can still show variation in maturity levels. No two component whiskies are the same. That’s why we keep records of the blend ratios ourselves and regularly confirm them to test their suitability for Yamazaki 12 Years Old. This process is repeated over and over again.

Hiraga: I see. From what you’ve told me, it seems that the work of the blender is quite similar to mine in assembling mechanical watches in many ways. I have been involved with the Grand Seiko Kodo, our most prestigious complication watch, since the initial development phase.

An essential part of product development is checking whether the drawings of our movement design team will result in a watch that performs as intended, with the necessary precision and functionality. Movement design often requires a lot of trial and error. It is hard to know whether the parts are correct until they’re actually manufactured based on the drawings and assembled.

During assembly, we need to take into account a range of specific factors-whether the required precision is achieved, whether each part is easy to handle, or how each part should be handled. If something is difficult to work with or cannot be assembled properly, we provide feedback to the design team so they can make the necessary corrections.

Koshiishi: You evaluate the design by creating a prototype and checking whether it works as intended, is that correct? Are you also responsible for evaluating the visual aesthetics of the design?

Hiraga: No, the visual aesthetics are not part of my responsibility. Having said that, for models with a see-through case back, where the movement is visible, we do pay careful attention to maximize visibility. It is important to be clearly visible from any viewing angle. Of course, high accuracy remains the top priority.

Koshiishi: That really does sound just like what we do as blenders. What we know as whisky is made up of two elements that work together: the bottle design and the whisky itself—what we call the contents. We are extremely particular about the whisky that goes into the bottle. We don’t just churn out the same products every time; we are always thinking, “Last time we did it this way, what if we change this part just a little? Maybe it’ll taste even better.” That mindset of constant improvement is something we try to bring to every blend we create.

Hiraga: I imagine that tasting plays a key role in that process.

Koshiishi: That’s right. From selecting the component whiskies to blending them, the tasting process requires intense concentration. If every little detail of each component whisky isn’t carefully examined, important elements, good or bad, can easily be overlooked. That’s why we go over each sample again and again, paying incredibly close attention to every little characteristic. We can’t afford to overlook anything. We are always looking to improve our blends, making each one better than the last in terms of what we call bimi-hinshitsu or “Quality Craftsmanship.” And that demands an exceptionally detailed understanding of every component whisky.

Hiraga: Do you bring together the opinions of all the blenders in the team when finalising the product?

Koshiishi: Each of us has responsibility for different blends. One person handles Kakubin, another looks after Reserve, and so on. We each focus on our blends. But if we work separately, there’s a real risk that one day, each product might go beyond its taste range. And that’s something we want to avoid.

That is why one of the most important parts of our work as blenders is to clearly define which component whiskies belong to Kakubin, which to Reserve, and so on. We share those insights during our inventory count of component whiskies, and I believe that’s a crucial part of our training and development.

Hiraga: Yes, it’s the same for us. When we’re working on a new product, several of us will get together to share recent findings and updates about accuracy. Then we talk about how we tackle the issue and figure out the best way forward. It’s not something that can be done all by oneself. To create something really good, everyone has to work together with a shared sense of purpose.

Koshiishi: That’s true. The difficult part with whisky is that the tasting records ultimately rely on memories. There’s a limit to how much can be quantified.

Let’s take this opportunity for you to experience a tasting of component whiskies.

Hiraga: I’d be delighted. Thank you very much.

Koshiishi: Whiskies generally develop the best aroma at around 20% alcohol content. That is why, for tastings, we generally dilute them to around 20%.

First, bring the glass up to your nose and smell the aroma. The aroma is your first source of character for the component whisky. At Suntory, we place great importance on aroma. Suntory whiskies are known for their excellent aroma, so this is a key consideration in blend formulation. Don’t you notice a rather refined, elegant aroma as you bring the glass close to your nose?

Hiraga: Yes, I do!

Koshiishi: Next, take a sip and hold it in your mouth. What we’re looking for is a nice, smooth taste that lingers for some time. I’m hoping it feels smooth to you.

Usually, we sip and spit during tastings, but not today. Today we’re going to swallow the whisky!

Hiraga: How much should I put in my mouth?

Koshiishi: About three milliliters. Let it settle on your tongue for a moment, then swirl it around in your mouth. The aroma really develops; even inside your mouth, you should be able to sense the aroma.

Hiraga: (takes a sip) This is a great whisky!

Koshiishi: It sure is. Mr. Hiraga, you look really satisfied!

Hiraga: But I suppose just being “great” isn’t quite enough when you’re making a blend. I realized how much the job of the blender depends on precise senses of taste and smell. How does one pass those skills on?

Koshiishi: Yes, it’s definitely an art form. There are blending formulas and written notes, of course, but relying on those alone doesn’t mean we can create a blend. The key is to be able to achieve both bimi-hinshitsu (Quality Craftsmanship) and maturity. But ultimately, it comes down to how to use our sense of taste and smell. That can only be learned by spending several years working under an experienced blender. There’s no doubt in my mind that it takes years, not months, to truly develop the skills of a blender.

Hiraga: How exactly does one learn it in practice?

Koshiishi: Well, for example, each team member might create their own test blend and submit the formulation sheets for review. By looking at the proportions, I can often tell if the blend will be dominated by a certain aroma or if the component whiskies seem like a poor match. But I don’t like to give too much away. I usually just say something like, “It’s not quite right, is it?” I believe it’s more valuable for them to face the component whiskies themselves and think through the process using their own sensory judgment.

Then they revise the formulation, and I’ll say, “It’s still not quite there yet.” We go back and forth like that for a day or two. It’s all part of the process.

Hiraga: Was it the same for you when you started as a blender?

Koshiishi: They first assigned me to work on a brand called Hakushu 12 Years Old. I tried to copy what my senior did, choosing component whiskies and making up blends, lining up the glasses along the table. My senior would walk past and silently pick up one glass, then another, without saying a word. I’d be standing there wondering what it all meant. After all, the glasses all looked pretty much the same to me. I was concentrating really hard, watching his hands to see which ones he picked out and which he didn’t (laughs). It turned out the ones he picked were whiskies not to be used, for creating Hakushu. It took me a long while to figure that out.

I imagine that watchmaking also requires a refined use of the senses.

Hiraga: In watchmaking, a lot of the techniques rely on the sensitivity of our fingertips. The core part of the mechanical watch is a hairspring, which is the most critical spring because it controls the accuracy. Grand Seiko’s hairspring is extremely thin and delicate, just 0.03 mm thick. We have to shape it exactly to match the design, but we don’t really know how to pick it up and handle it properly until we actually try it.

Koshiishi: That sounds like it requires a lot of experience.

Hiraga: It really does. The hairspring is metallic and has a certain elasticity, so when we pick it up with tweezers, we can feel a very slight bounce-back sensation through the tips. We have to keep that feeling in mind as we shift it inside, learning through experience how applying a certain amount of force can cause everything to shift by just a few microns. That can’t really be learned just by watching and listening to others. As they say, experience is the best teacher.

Koshiishi: It sounds like a very precise and delicate task, which requires an extremely fine sense of touch. You might not even realise anything’s wrong just by handling it.

Hiraga: Sometimes I’ll say, “Do you feel that slight sensation in your fingertips just now?” But some people don’t feel it at all. That usually means they are still unsure about where to hold it and how much pressure to apply. In those cases, all they can do is practice diligently with thousands of different parts, if not tens of thousands. It takes years to develop their own technique.

Koshiishi: It is not as simple as just assembling a watch by following a drawing, right? And it’s the same with putting together a whisky blend.

Hiraga: Japanese whiskies, such as the legendary Yamazaki from Suntory, are today highly acclaimed around the world, even in Europe, where whisky originated. What do you believe is the primary appeal of the ever-popular Yamazaki?

Koshiishi: I think it all began in 1923, when Shinjiro Torii began building the distillery here to craft a world-class whisky designed for the delicate Japanese palate. More than 100 years later, we are still committed to pursuing that original ideal.

Hiraga: And that’s reflected in your commitment to always striving to make each blend better than the last.

Koshiishi: When demand for whisky dropped in the late 1980s, we invested in upgrading the fermentation tanks and pot stills at Yamazaki Distillery. This flew in the face of conventional thinking: most companies would have focused on efficiency improvements during hard times, but at Suntory, we always put quality first. We’ve been making whisky for the Japanese palate for the last 100 years, always with an unwavering commitment to quality. I believe that our dedication is now being recognised internationally, as reflected in the number of awards we‘ve received at global competitions

Hiraga: So you would say that the commitment to quality rather than efficiency is the key defining characteristic of Suntory Whisky.

Koshiishi: The whiskies produced after the major upgrade were matured in casks for over ten years; then, in 2003, they were released as Yamazaki 12 Years Old, which went on to receive several prestigious international awards. We saw that as the ultimate recognition of our commitment to bimi-hinshitsu, quality craftsmanship at Suntory.

Hiraga: At Grand Seiko, too, quality is a top priority, but in our case, that means precision. That’s why even today, every Grand Seiko model is assembled by hand, not by machines.

For example, pivots and their corresponding holes in each gear wheel are smaller than those in most conventional watches, so they need to be fabricated as snugly as possible to achieve high precision from every angle and in any position. There’s virtually no margin for error. The design of a Grand Seiko movement requires hand assembly; machines can’t handle it.

Years of experience have naturally led to a refined sensibility. Once the ability to position parts with sub-millimetre precision is acquired, a watch can be assembled much more quickly. Any irregularity becomes immediately apparent, like a slight bend in a part or an end not fitting precisely. The kind of finely tuned sensitivity needed for precision watchmaking can only be developed through years of experience.

Koshiishi: Has your company always had a commitment to quality first since the time of its founding?

Hiraga: Certainly. Grand Seiko was born in 1960, driven by a mission to create the world’s finest watch. We have remained true to that ideal for over six decades, consistently producing highly accurate watches with quality as our top priority.

Even when mechanical watches are no longer the mainstream globally, we have remained committed to preserving the craftsmanship of watchmaking and have continued to produce sophisticated, high-precision movements. And we believe this is what underpins our reputation for excellence, not only in Japan but around the world.

Both of us, Grand Seiko and Suntory, have also been committed to preserving traditional techniques over the years. I believe that this focus on quality as well as efficiency, along with a sincere dedication to the fundamental art of manufacturing, has been the driving force behind the success of both our companies. Our conversation today has given us a renewed determination to pass on to the next generation everything we have learned from our predecessors.

Meticulously composed of rare malt whiskies all aged over 25 years in casks such as Japanese Mizunara oak, Spanish oak, and American oak casks. Characterised by aromatic wood accents and rich aromas of ripened fruit, with gentle sweetness and depth of acidity and an exceptional finish. Awarded the Supreme Champion Spirit prize for overall excellence across all categories at the 28th edition of the highly prestigious International Spirits Challenge (ISC) in 2023, in recognition of the multifaceted complexity of flavours and aromas not normally found in a single malt whisky. This honour established Yamazaki 25 Years Old as the world’s finest whisky.

A masterful blend of creamy yet powerful malt whisky aged for at least 25 years, densely peated-malt whisky, and Spanish oak cask whisky infused with full-bodied fruit aromas. Characterised by a smooth, mellow taste which comes from a long, thorough marriage process.

Awarded the “Trophy”, the top award among the Japanese Whisky category at the 27th International Spirits Challenge in 2022.

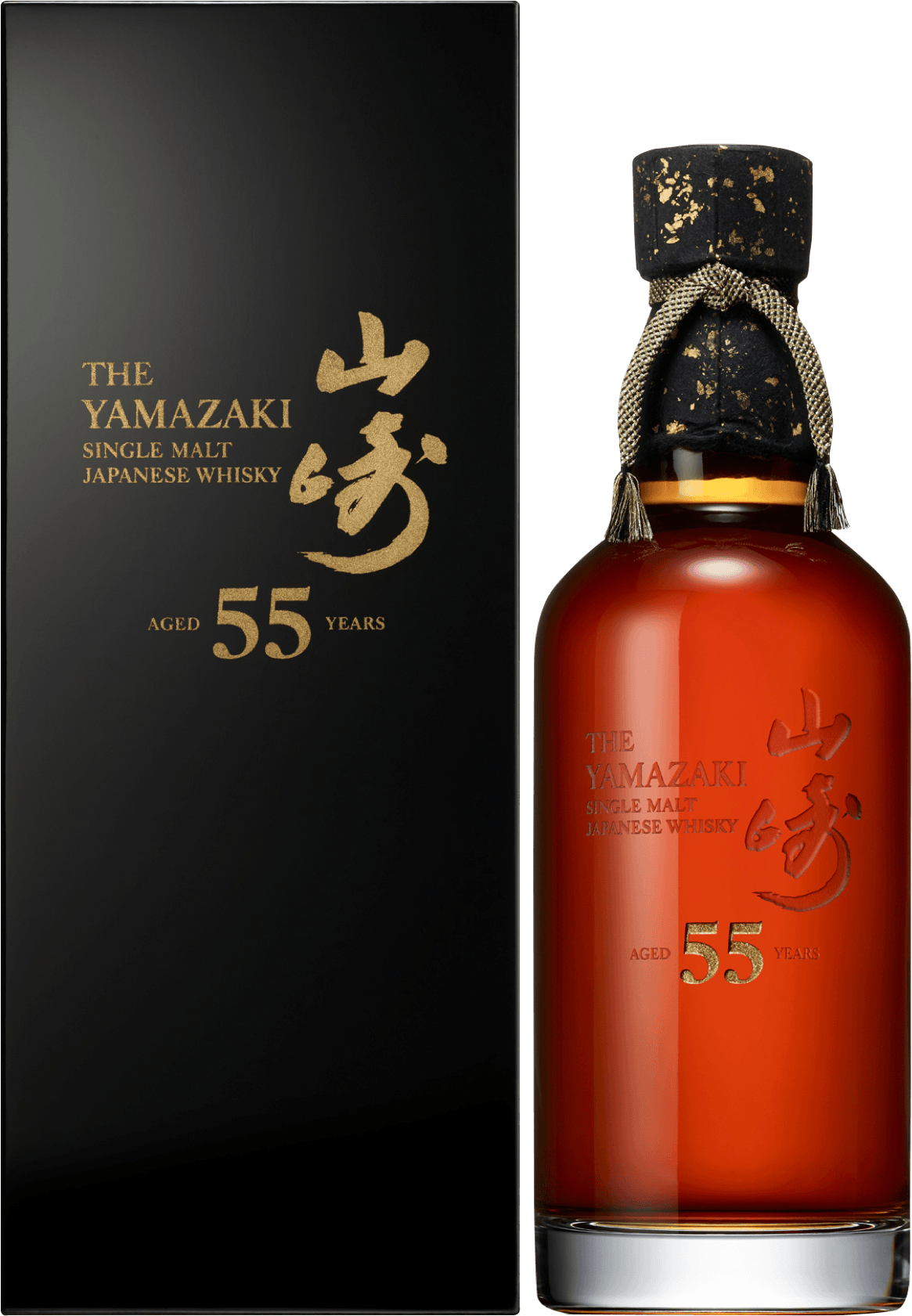

The ultimate drop for whisky aficionados, released in 2020 with a limited run of just 100 bottles made available through a lottery. The oldest whisky ever produced by Suntory, a blend of single malt whiskies distilled and stored no later than 1964, then aged for over 55 years. Characterised by a complex aroma with hints of agarwood and sandalwood, typically associated with Japanese Mizunara cask ageing. On the palate, it transforms into a woodiness that encompasses both sweet and bitter notes, leading to a rich, full-bodied finish with a subtle hint of bitterness.

Grand Seiko Kodo Constant-force Tourbillon

The Kodo is the ultimate mechanical complication watch. Released in a limited edition of just 20 pieces, with only seven for Japan. It is the first watch ever to successfully combine highly complex constant-force and tourbillon mechanisms comprising over 100 components on a single axis to achieve next-generation standards of efficiency, stability, and precision.

Launched in 2022, Kodo was the first-ever Grand Seiko mechanical complication watch. That same year, the newly released Grand Seiko Kodo SLGT003 model was awarded the Chronometry prize at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève for outstanding precision in a wristwatch. Whereas the previous model was designed with the theme of evening twilight, the SLGT005 was inspired by daybreak, and the morning sky just before dawn.

Joined Suntory in 1982, starting his career in the Hakushu Distillery. Became a blender in 1999. Involved in creating numerous products including Yamazaki 50 Years Old, Yamazaki 55 Years Old, Hakushu 18 Years Old, Hakushu 25 Years Old, and Hibiki 12 Years Old. Koshiishi has played a major role in enhancing the global reputation of Suntory whiskies, with key accolades including the Trophy first prize in the Japanese Whisky category for Hakushu 25 Years Old at the International Spirits Challenge (ISC) 2022 and the Supreme Champion Spirit overall excellence prize for Yamazaki 25 Years Old at ISC 2023.

Joined Seiko Instruments & Electronics Ltd. (now Seiko Instruments Inc.) in 1989. Won the national watch repairing contest and the Minister of Labour Award in 1995. Certified as a National First Grade Watch Repairer in 2003. Awarded the title of Contemporary Master Craftsman by the Japanese government in 2015, followed by the Medal with Yellow Ribbon from the Cabinet Office in 2020. Currently works for Seiko Watch Corporation.

Photography = Norio Kidera Text = Akane Yoshikawa